Introduction

For many, religion is an idea whose time has passed. Science, which has split the atom and traveled to distant planets, has shown us no sign of a ‘creator God’ worthy of acknowledgement. The technological progress of our era has reduced religious belief to a helpful superstition at best, or a dangerous flaw at worst. Either way, its relevance to our future has recently been put into question.

Some of us may even be sympathetic to the following quote, from the celebrated mathematician Bertrand Russel:

“Religion prevents our children from having a rational education; religion prevents us from removing the fundamental causes of war; religion prevents us from teaching the ethic of scientific co-operation in place of the old fierce doctrines of sin and punishment. The knowledge exists by which universal happiness can be secured; the chief obstacle to its utilization for that purpose is the teaching of religion. It is possible that mankind is on the threshold of a golden age; but, if so, it will be necessary first to slay the dragon that guards the door, and this dragon is religion.” (Has Religion Made Useful Contributions to Civilization?) 1930

What has caused this decline in the status of religion? I think the culprit has been scientific materialism. This is a philosophical system which states that physical objects and processes, the kind studied by natural sciences, are all that exist. Crucially, what this means is that even consciousness itself is reducible into the mere interactions of particles. This will be an important point that I’ll return to later on.

Scientific materialism is both an ontology (study of being) and epistemology (study of knowledge). Its ontology states that what is fundamentally real is the physical existence of particles, energy, and so on. For the scientific materialist, a ‘complete physics’ that could describe the behavior of every particle in the universe would essentially reduce the emergence of all higher-order structures (molecular interactions, organ systems, but also subjective experiences and social forces) into nothing more than complex arrangements of this underlying material substrate. The principle reality that exists is a physical one.

The epistemology of scientific materialism is even more relevant. This is the claim that what is fundamentally true is that we live in the kind of ‘material arena’ that is explicated by its ontology. Because of this, we can only be certain about the truth of a proposition if we find that it corresponds to external reality. This is what can be demonstrated by the scientific method: that is to say, by observable, replicable, and universal data obtained by experiment. When someone says ‘I want to eat’, the scientific materialist reduces the truth of this proposition to the existence of some neurochemical signals in his brain; similarly, when someone says ‘God exists’, the scientific materialist posits God as some positive externality in order to assess its truth value.

Scientific materialism is not just a topic for the intellectual patter of philosophers and theologians. It is a mindset which informs our most intimate experience of the world. This is perceptible in the rise of the ‘new atheists’, a group of scientists and philosophers who conducted a popular critique of religion in the early 2000s. The most compelling anti-religious arguments put forward by these thinkers were deeply informed by scientific materialism.

This is best encapsulated, I think, by the recent popularity of the agnostic position. This is the claim that one does not subscribe to a belief in God on the basis of insufficient evidence. God might exist, but until there are data to show it, the agnostic cannot hold the statement ‘God exists’ as true.

The notion of holding-to-be-true, or Fürwahrhalten, was developed by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant. He numerated 3 distinct modes by which a proposition can be held to be true:

Opinion is such holding of a judgment as is consciously insufficient, not only objectively but also subjectively. If our holding of a judgment be only subjectively sufficient, and is at the same time taken as being objectively insufficient, we have what is termed belief. Lastly, when the holding of a thing to be true is sufficient both subjectively and objectively, it is knowledge. (The Critique of Pure Reason)

We say that someone has an opinion when there are no objective facts to support them, nor any subjective certainties on their part. Under some scrutiny, they might reasonably be made to change their opinion. For example, someone’s view on abortion may be vague and unelaborated: they would be right to preface their statements with, “this is just my opinion, but …”

Belief, on the other hand, involves subjective certitude but lacks objective sufficiency. It is in this category that we include faith. For example, someone may as part of their religious faith believe that the remnants of Noah’s arc exist somewhere out there, waiting to be discovered. In this case, his faith in God would be the origin of several religious beliefs, which he holds to be true ‘in his heart, not his eyes’, so to speak. This kind of holding-to-be-true is what Kant identifies as belief.

But still, the religious believer cannot claim to know that the object of his belief is true. In order for a proposition to be elevated to the status of knowledge, it must gain objective sufficiency. In other words, in order for a holding-to-be-true to be justified as knowing, empirical demonstration is required.

So, what can be said about the agnostic, who refuses to hold the proposition ‘God exists’ as true? It demonstrates that they await the induction of a proposition into the realm of knowledge in order to engage with it as true. The agnostic looks at a religious believer and says, “I cannot be them, for I am drawn to objective certitude”. In more familiar terms, the agnostic is incapable of preforming a certain leap of faith, because his criterion for holding-to-be-true is that a proposition be known.

Now, it is my thesis that this inability is predicated on the scientific materialist perspective from which the agnostic speaks. This is a perspective which fundamentally limits a person’s holding-of-truth to what can be empirically verified. “Show me the evidence”, that popular response to religious faith today, is the most recognizable calling card of scientific materialism. To use Kant’s terms, this means that the scientific materialist can only accept what is known to be true and not what emerges as true by faith.

How can we understand this idea of emerging-as-true? First, we need to recognize that the type of truth that results from faith — religious truth — is different from our familiar concept of scientific truth. Owing to its independence from objective facts, religious truth might best be described as a form of subjective truth. That being said, there are certainly truths about the world which are not influenced by one’s individual character or mindset: subjective truths cannot and should not interfere with objective truths. The sky is blue regardless of your subjective orientation towards existence.

But subjectivity opens up a new locus of truth: truths which are predicated by a certain subjective orientation, or put in other terms, truth which become self-sustaining once a given subjective orientation is provided.

This does not have to be so mystical. We can find an example in the everyday question, “do things happen for a reason?”. Here’s an answer I find convincing: if you live your life believing that things happen for a reason, then things happen for a reason. In other words, when you filter through the otherwise random and contingent events of life on the condition of anticipated meaning and purpose, it so happens that a constellation of events come together which, considered retroactively, can be said to have ‘happened for a reason’. The opposite subjective engagement with the world, on the other hand, assembles no such constellation. Subsequently, a more nihilistic person creates the conditions of their own belief that nothing happens for a reason, that everything is random, and so on.

We also find an example of this phenomenon in love. Being in love is a strictly irrational position: the reasons for my infatuation with a girl aren’t reducible into a series of qualities, say, that were already present when I first met her. After all, I couldn’t go around a room of girls with a checklist and ’cause myself’ to fall in love with the one who fits the most of my preferences. Rather, the conditions arise once something unspeakable happens: the ‘fall’ of love, the primal moment of subjective engagement. Only after the fall do we create the qualities which we can point to, which then become already-present, retroactive conditions of themselves.

And here we discover the true meaning of Pascal’s wager. When Blaise Pascal suggests to the religious doubters that they ‘do it anyway’, and walk through the actions of a Christian despite their skepticism, this is not simply an insurance policy in case they are wrong about God. In other words, it is not simply a utilitarian argument that claims it is in your self-interest to do so. Rather, Pascal is identifying that in matters of religious faith, activity is in some sense primary to the cognition. In Pascal’s own words: “Habit provides the strongest proofs and those that are most believed. It inclines the automaton, which leads the mind unconsciously along with it.” What Pascal is saying here is that, as automata, our embodied activity comes first, and our cognition comes after. The truth is often a function of the activity, and not so much the cognition.

This dimension of truth — which involves the subjective orientation of the observer, not just what is ‘objectively there’ — is the dimension of truth which we must grapple with when speaking of religious faith. Faith is a radical experience which transforms the dimension of truth in a way that cannot be encompassed by the scientific materialist perspective. In order to clarify this, it will be necessary to explore this new dimension of truth and identify it for what it is: a pragmatic form of truth.

Two modes of truth: Jordan Peterson vs Sam Harris

The distinction between scientific and religious truth reveals a more fundamental distinction: that between a correspondence theory of truth and a pragmatic theory of truth.

Correspondence theories of truth claim that truth is a measure of correspondence with reality. Scientific materialism is clearly in line with this perspective: a proposition’s truth value is fundamentally related to material constitution. For the scientific materialist, all propositions which can be held true with certainty necessarily refer to the external world.

Pragmatic theories of truth, on the other hand, maintain that truth can only be specified with regards to a certain aim. According to this theory, truth always stands in relation to a particular function on the part of the inquirer. If you set a goal, and hold some proposition as true in pursuit of that goal, its achievement allows you to state that your proposition was true enough for the outcome.

Sam Harris is arguably the most popular scientific materialist in America. No surprise, then, that he is one of the four ‘new atheist’ thinkers I mentioned earlier. Nowhere is Harris’ materialist philosophy more apparent than in his thorough refutation of free will, an endeavor towards which he dedicated an entire book. As a neuroscientist, Harris is quick to maintain that our mental states are simply the result of material interactions in the brain. Because of this, they are — in theory — perfectly predictable by the tools of science. Thus, for Harris, the statement “free will exists” is false because the phenomena of free will can be reduced into a material substrate which follows known laws. How can free will remain as a metaphysically distinct label when your decisions are subject to the same fundamental laws that govern the motion of objects?

For Harris, then, what is true is what corresponds to external reality. Even the truth of subjective experiences, like the feeling of pain or sensation of smell, must be subjugated to the material conditions from which they emerge. As such, the existence of conscious states is reduced to its underlying neurobiological substrate. This is what allows him to deny the existence of free will: since ‘free will’ is fundamentally the movement of particles, and their laws are determined, there cannot be free will.

Jordan Peterson is a Jungian psychologist who has been leading a push for thinking in more pragmatic terms about the nature of truth. His 1999 work Maps of Meaning is a detailed elaboration on the idea that, as humans, our reality is fundamentally structured like a narrative. Accordingly, it is filled with challenges against the scientific materialist outlook, which he claims limits the world to what exists, at the expense of what to do about what exists. Subsequently, his ethic is founded on the claim that what is fundamental to our experience is a moral injunction to confront chaos and strive towards the ‘ideal’, which he often uses synonymously with the concept of heaven.

For Peterson, then, what is true is what facilitates our aims as individuals in the pursuit of leading ideal lives. Certainly, Peterson sees scientific materialism as an unbelievably valuable tool in this regard: it has given us industrial machines, antibiotics, computers, and many more technologies which have greatly improved our quality of life. But for Peterson, our primary reality — what is fundamentally true — is not the ‘material arena’ of objective facts which science elucidates. Rather, it is the transcendental value structure which gives objects their valence and guides our embodied activity in an automatic and often-times unconscious way.

These two thinkers, established as they are in their own right, nonetheless subscribe to strictly irreconcilable ideas on the nature of truth. It’s no surprise, then, that when they connected for the first time in early 2017 they became mired in a staunch and seemingly unsolvable disagreement. In a now-infamous exchange on Harris’s podcast Waking Up, Peterson insisted that our Darwinian origin influences how we should consider truth. Espousing the pragmatic position, Peterson claimed that we are structured — biologically, psychologically, and socially — to survive and produce progeny. Therefore, from a pragmatic perspective, a given fact about the world may be true or false depending on how well it achieves the aim of survival.

In other words, since our very capacity to model the world as a materialist arena for phenomena developed in an evolutionary setting, what is ‘primary’ about our connection to reality is not the model, but rather the evolutionary drives which establish and provide valence to that model. In this way, Peterson disassociates from the philosophy of scientific materialism which is at play in Harris’s discourse. Peterson himself describes this position as a statement that Newtonian truths — a term he uses to refer to scientific truths — are nested within Darwinian truths. In his own words:

“I don’t think that facts are necessarily true … [laughs] … I don’t think that scientific facts, even if they’re correct from within the domain they’re generated, I don’t think that necessarily makes them true. And I know that I’m gerrymandering the definition of truth, but I’m doing that on purpose, because I’m trying to nest truth within a Darwinian framework, which I think is a moral framework”

Quick to the defense of scientific truth, Harris evoked the intuition of his audience and insisted that some facts are true regardless of their consequences on our species. In other words, Newtonian truths are primary and Darwinian truths must be nested within them, not the other way around. He gives the following example to illustrate his point: the biochemistry of smallpox synthesis remains true whether we use it for the benefit of humanity or its destruction. If Peterson is insisting that a given proposition’s truth value relies on its influence on survival, then we have the paradoxical situation where the same scientific findings become false the minute they are used to destroy the population. To this compelling point, Peterson could only respond by arguing that, in the event it ushered in the apocalypse, the science of smallpox would not have been ‘true enough’. Harris was not satisfied by this answer and stood by his science-first view of truth.

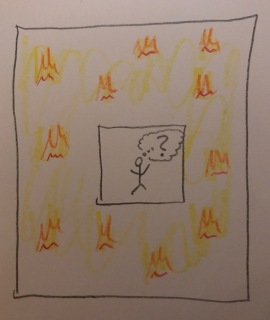

The burning house example

Through the long and laborious dialogue that ensued, there was a certain moment that I believe captured the essence of the disagreement. Peterson introduces the following scenario, which we may call the burning house example. If someone is sitting in their room unknowingly while a fire rages the house around them, should we question the truth of their proposition that ‘there is no fire in this room’? Well, it would certainly be a lousy theory, as Peterson claims. Even so, argues Harris, we cannot depart from the obvious notion that it is still true. Certainly, we can say that this truth is an incomplete picture of the world, or even that it is detrimental for the observer, but why should we doubt our intuition that the proposition itself remains true?

Here is where, I think, we can start to make sense of Peterson’s position, and rescue it from the arguments Harris put forth. We begin by elaborating on the proposition ‘there is no fire in this room’. All things considered, (especially on an evolutionary scale), this is a very specific proposition, and if we were to be more accurate, we can identify the statement as being of the type ‘there is no fire in this location X at this moment in time Y’ out of many possible Xs and Ys. Now, the specificity of this statement reveals it as a subcategory of a more general statement, namely, ‘there is a fire’. To summarize, let’s say that ‘there is no fire at X place in Y time’ is a species of ‘there is a fire’, insofar as it serves as a specification of the second proposition and coheres with its overall motivation (namely, to know whether or not there is a fire).

In turn, we might imagine that ‘there is a fire’ is itself a species of the proposition ‘there is a threat’, which in turn might be a species of ‘there is something to avoid’. In this way, we can identify the cause of the statement ‘there is no fire in the room’ to be a desire to know ‘is there a threat?’ Now, ‘there is a threat’ is a proposition which is true of the person in the situation, although he is not aware of it.

We can now see why Peterson is so adamant on bringing up Darwin: the objective propositions we make about the world can be traced back, perhaps, to a primordial hypothesis-testing mechanism whose primary motivation was to ensure the survival of the organism. And we can now understand Peterson’s statement that “if [a proposition] doesn’t serve life, then it’s not true.” We simply need to keep in mind that the propositions we put forth always serve an underlying purpose; they are always species of motivations which we embody as a feature of our evolution.

Thus, a proposition’s coherence to its cause-of-speech (which brought it into existence in the first place) in some sense supersedes the objective truth value of the proposition itself. This allows us to conceive of the truth value of a proposition as being related to the aim of the inquiry which produced it. It is true, pragmatically-speaking, if it is “in the spirit” of maintaining the aim specified by its cause-of-speech.

Now, Harris might respond here by saying that these considerations about a statement’s context are unnecessary. This would be a claim that the proposition can be divorced from the motivation underlying its articulation. But the fact of the matter is, as humans, we cannot access our world outside the house of language. Or articulation of propositions is a kind of speech, and speech is always motivated. We simply cannot stand at an objective distance from facts about the world: we do not encounter ‘naked truths’, rather, this encounter is always predicated on our motivations.

We can summarize by saying the following. Propositions are always statements, and statements are always nested within motivations that act as causes-of-speech. Therefore, a proposition can be assessed not only on its correspondence with external reality, but on its coherence with its cause-of-speech. Then, we can endeavor (like Peterson) to follow the “trail of desire” for a given statement down to its most Darwinian drive: a struggle for survival.

With this clarity in mind, we return to the question at hand: should we, given the fire that rages around the house, call into doubt the truth of the statement, ‘there is no fire in the room’? It appears we can, because answering ‘no’ to that question (while objectively true in a ‘local’ sense) betrays the general motivation behind its articulation: its cause-of-speech, ‘there is a threat’. The answer to the question ‘is there a fire in this room’ may contradict the more general, and metaphysical, issue of ‘is there a threat to be avoided’. And it is in this sense that we can start to speak of objective truths as being pragmatically false: when they betray the cause-of-speech which governs their articulation in the first place.

Here, we can reintroduce Peterson’s idea that the ultimate truth is a value system which guides your embodied activity. The valence we place on objects and situations certainly influences our movement and engagement with the world. But it also guides our utterances: indeed, our transcendental value system can be thought of as a nested series of causes-of-speech which guide us towards making statements. And crucially, it also guides us in endeavoring to understand the world and make observations about it.

We can now return to Harris’s counterargument about smallpox. If we start with the idea that a mad scientist who concocts a weaponized smallpox virus is making propositions which betray their causes-of-speech — which betray the innate value system from which he operates — then we can say that those propositions are false insofar as they are self-defeating; they are species of more underlying motivations which are not being satisfied by them. We are then given ground to conclude that the scientific facts behind his biochemical endeavors are objectively true but pragmatically false. To put it in more rigorous terms, his inquiries into the biochemistry of smallpox was a species of a more underlying question which became self-defeated by the result of his action.

We might even say: all of the biochemist’s facts are wrong because he was not, in the first place, being true to himself.

Ironically, Harris was close to this solution when he said, “there are an infinite number of ways to explore the universe.” The consequence of this fact is that every time we ‘probe’ the universe and come back with a proposition, we can always ask the question, “but why did we chose this investigation and not another?” In other words, the infinite possibility for our engagement with the universe means that any engagement we do have always contains an underlying motivation or desire.

Here, the psychoanalytic theory of Jacques Lacan will be very useful to us. According to Lacan, truth cannot be described as a qualifier of propositions. Unlike analytical philosophers and logicians like Bertrand Russel (whose quotation we read earlier), Lacan did not believe that the ‘truth’ of a given proposition could be described using a metalanguage. Instead, Lacan argued that the truth operates on the level of a cause-of-speech.

We can illustrate this by exploring Lacan’s solution to an ancient problem: the liar paradox. Lacan solves the paradox — is the proposition ‘this statement is a lie’ true or false? — by saying the following. On the level of the statement, the subject is lying, since he claims himself to be lying. But on other level, the subject is telling the truth insofar as he is aiming at something by saying he is lying. Thus, the truth of the statement is not operating on the level of the proposition, ‘I am lying’, but rather on the level of the motivations which cause it to be spoken in the first place.

In a similar sense, to determine the pragmatic truth of a proposition, we must contextualize it with regards to the value structure which produced it in the first place. Only there, in the aim behind the value structure, can we assess the ultimate truth of the proposition, rather than in its correspondence to the objective world.

Towards a characterization of religious truth

Armed with this understanding of pragmatic truth, we can now distinguish between scientific and religious truths more clearly. Whereas scientific truths deal on the level of the proposition, attempting to relate its contents to external reality, religious truths exist on the level of causes-of-speech, which are conditions of possibility for the proposition in the first place. Specifically, religious truths deal with the value structure which guides our embodied action, which includes proposition-making in the category of speech.

These two dimensions of truth are in dialectical opposition to each other. The scientific-materialist objection to religion, and more specifically the proposition ‘God exists’, treats its truth according to correspondence theory and therefore immediately posits God as some positive externality that could someday be detected by empirical investigation. This explains the comfortable position of the agnostic today: since their understanding of religious truth is limited to the correspondence theory, they cannot help but interpret God as some potential data point which we have yet to observe.

But again, this characterization of religious truth simply misses the mark. The domain of religious truth deals with the pragmatic dimension, not the objective one. We cannot take a religious statement, treat it as a proposition, and apply a correspondence theory of truth to find its correlate in external reality. Rather, religious truths are transcendental, axiomatic conditions of our embodied activity, and more specifically of our discourse itself. These are conditions that permeate our experience of the world, and can also be understood as the most fundamental aims in a motivational hierarchy which gives the objects of their world a kind of moral valence.

To summarize these remarks, I can make the following (rough) outline:

- We are, fundamentally, speaking-beings; therefore

- All propositions are statements;

- All statements have a cause-of-speech;

- The pragmatic truth of a proposition is related to the aim of its cause-of-speech;

- Religious truths are pragmatic; therefore

- Religious truths are related to the aim in articulating them

It seems intuitive that there are certain aims with regards to our lived experience which can only find their resolution in the adherence to certain beliefs. These can be regarded as beliefs which materialize a certain value structure, and therefore organize our embodied action in a way that is conducive to those underlying aims.

Which begs the question: what might be an example of a transcendental axiom of embodied activity, which we could count as a religious truth? I’ll put one forward in an upcoming article.

This is borderline gibberish due to it being so poorly worded.

“We are, fundamentally, speaking-beings; therefore”

What does this mean? Do you mean that our conscious cognition is based on words?

—

“All propositions are statements;”

ok

—

“All statements have a cause-of-speech;”

What does this mean?

—

“The pragmatic truth of a proposition is related to the aim of its cause-of-speech;”

What does this mean? Is a proposition pragmatically true if it is the cause-of-speech (whatever this means)?

—

“Religious truths are pragmatic; therefore”

They are pragmatic in what sense?

—

“Religious truths are related to the aim in articulating them”

What does this mean? What is the aim in articulating them, is it saying them makes it true?

—

The extent some people will go to to try and rationalize their irrational beliefs is both entertaining and frustrating to observe.

LikeLike

“they are pragmatic in what sense?” in the sense I spent 2,000 words describing to you. besides that though, I think your first criticism is valid: I didn’t elaborate on the Lacanian idea of the speaking-being in this article. I invite you to wait for the next one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very, very nice content. I love how you neutrally described two worlds that have divided billions–and will continue to!

Looking forward to your next article.

LikeLike

thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

https://aeon.co/ideas/believing-without-evidence-is-always-morally-wrong

LikeLike

thanks for the link! here’s a possible counterexample though: why believe that other people have minds like yours when, strictly speaking, there’s no scientific evidence of this (the infamous hard problem of consciousness)? And yet this is an automatic belief which is not only sustained, but necessary for normal development. I think this illustrates that there are beliefs that we act out: which exist on a practical level as opposed to a scientific one

LikeLiked by 1 person

This seems to be a complete dodge on your part to avoid responding to the points made in the article. Disappointing but not surprising.

Truth doesn’t have a prefix of their or our.

If you are unwilling or unable to have an honest discussion about your essays and address counter-arguments then it might be best to eliminate the comments section so that people wanting a discourse do not waste their time.

LikeLike

LikeLike

Strongforce, why didn’t you reply to prophemy’s example? I didn’t follow you when you said prophemy was dodging the article. Prophemy offered an example of a belief for which we have no evidence and yet which it seems we must believe. Doesn’t that call into question Clifford’s claim that we only ought to believe things for which we have evidence? And where is his evidence for this? He just seems to assert it passionately, much like Dawkins does in our own day. I would be interested in what you make of prophemy’s example.

I have grown fond of William James’s famous reply to Clifford:

“The greatest empiricists among us are only empiricists on reflection: when left to their instincts, they dogmatize like infallible popes. When the Cliffords tell us how sinful it is to be Christians on such ‘insufficient evidence,’ insufficiency is really the last thing they have in mind. For them the evidence is absolutely sufficient, only it makes the other way. They believe so completely in an anti-Christian order of the universe that there is no living option: Christianity is a dead hypothesis from the start.”

From The Will to Believe, section V. (https://www.mnsu.edu/philosophy/THEWILLTOBELIEVEbyJames.pdf)

LikeLiked by 1 person