Last week I attended a gathering hosted by the Interfaith Youth Core, a non-profit organization dedicated to advancing dialogue between members of diverse religious backgrounds. Specifically, the IFYC seeks to encourage religious pluralism in America’s college campuses by supporting student groups in navigating the difficult and sometimes treacherous waters of interfaith relations. Their focus on higher education is intended as a way to influence the American public more broadly, so that the standard of religious discussion and cooperation between faiths can be elevated on a national level.

American society is certainly a unique cross-section of human history. We are living in an era when religious identity is no longer the primary factor determining our affinity groups. This is especially true in urban centers. Our friends, neighbors, and coworkers are often times from a religious background which is completely removed from our own. Much to the angst of the political right, there no longer exists a shared Christian fabric underlying our etiquette and culture. In true cosmopolitan fashion, our allegiance is not so much to a specific creed but rather to our community as a whole, which comprises faiths of all kinds.

The IFYC is one of many movements that are emerging to address these societal developments and encourage us to position ourselves accordingly. Diversity does not always come easily; there will certainly be difficulties along the way. As part of one of their workshops, a speaker proposed the following case study in order to illustrate the subtleties and potential obstacles in the way of interfaith dialogue. I found it to be a compelling one.

A right to proselytize?

At the University of Illinois, a group called the Religious Worker’s Association allows faculty and staff to discuss their religious goals on campus in an interfaith setting. An Evangelical Christian organization called the Campus Crusade for Christ (Cru) had expressed interest in joining the group, before finding one slight but important disagreement. The RWA’s covenant lists among its stipulations that its members “will not initiate personal religious opportunities designed to draw persons from another religious community into [our] religious community”. Although this statement was probably intended to ease and facilitate the interaction between different groups, Cru found it completely antithetical to their cause. How can a self-described ‘crusade for Christ’ possibly agree to curtail religious proselytization?

Many attendees of the gathering agreed that transparency was a crucial factor in this situation. No matter what the established rules are, all religious groups should be open and honest about their intentions when engaging with others. Ironically, there’s something decidedly bad faith about an interlocutor who engages in a seemingly spontaneous dialogue, only to reveal that their intention was religious conversion all along. Certainly, disclosing one’s intentions is more than a religious issue: it’s an issue of common decency and conversational etiquette.

But there’s something more to this story. The discrepancy between interfaith discussions on one hand, and the injunction to spread one’s own religion on the other, is a topic whose resolution has theological underpinnings. In fact, it may just be one which encourages us to look upon the future of religious faith and dialogue.

A responsibility to proselytize?

I’ve always been fascinated by the inherent friction that permeates religious difference, even within the same group. Growing up, I knew many family friends who wear the hijab as part of their Islamic belief. Many of these consider the headscarf a personal choice and are largely indifferent to the choices of other Muslim women. But there are those who believe that the hijab is obligated for all Muslim women, and among these are some who conclude that it is necessary for salvation. Among these still, a small but vocal minority would attempt to convince non-wearers to dawn the hijab, lest their otherwise pious lives be wasted on a technicality.

This obviously comes at the universal chagrin of Muslim women who don’t wear the hijab. But frankly, I never understood this sentiment. My reasoning followed a simple logic. If someone who wears the hijab genuinely believes that the possibility of eternal hellfire rests in the decision to wear a cloth, isn’t it an act of grace — from their perspective — to try and convince as many people as possible? In fact, it seems immoral not to do so. A proper utilitarian might even argue that they should commit their lives to that pursuit.

And indeed, we often hear of religious people who do just that. During my years of undergrad at the University of Michigan, an Evangelical preacher would sometimes come to the Diag — a central area of campus — brandishing an enormous sign that warned us of hellfire. Adultery, gluttony, and blasphemy were among the charges he brought to our young ears, acting as a warner against our sinful ways. His attempts were, predictably, met with ridicule by us students. But again: if he genuinely believes that his message could mean the difference eternal bliss or eternal torment for even one person, isn’t he morally obligated to commit himself to this cause? And by extension, aren’t all Christians?

I’ve since moved on from this view, which I admit had all the undertones of an edgy 13-year old’s take. A quote from the Sufi tradition is what inspired my spiritual development on this issue. In the collection of his lectures and discourses Fihi ma fihi, Jalaluddin Rumi makes the case that all people, saints and non-saints alike, are proclaiming the praise of God. Although some do not appear to do so, each person is contributing to a divine end in their own way. To illustrate this, he compares society to the building of a tent:

Nothing exists that does not proclaim His praise. There is one praise for the rope-maker, another for the carpenter who makes the tent-poles, another for the maker of the tent-pins, another for the weaver who weaves the cloth for the tent, another for the saints for whom the tent is made (Fihi ma fihi, pg. 167)

As Rumi demonstrates, even those uninitiated to the Sufi cause are glorifying God by contributing to a society which can produce Sufi saints in the first place. In fact, it may not even be desirable that everyone should commit themselves to knowing God perfectly and becoming a saint. The structure of an organized and stable society, like the building a tent, requires various tasks which are not related to the end purpose but which are nonetheless intimately connected to it.

A similar idea is also represented in the Christian faith. Peter 4:10-11 speaks to the universality of God’s praise, although it may be manifested in different ways:

Each of you should use whatever gift you have received to serve others, as faithful stewards of God’s grace in its various forms. If anyone speaks, they should do so as one who speaks the very words of God. If anyone serves, they should do so with the strength God provides, so that in all things God may be praised through Jesus Christ. To him be the glory and the power for ever and ever. Amen.

What’s being articulated in these examples is the idea that an intellectual argument for God is not the exclusive demonstration of his existence. Daily tasks and other seemingly mundane activities can also be signifiers of the divine. This means that the ‘commoners’ of a given faith may not necessarily be charged with the task of proselytization, since their works can be considered a unique manifestation of divine presence. This gives interfaith dialogue some much-needed breathing room, since it can be reasonably argued that proselytization is the task of a gifted minority of religious believers, not a universal injunction.

But crucially, this does not account for that minority itself: those members of a religion whose expressed purpose is proselytization. This brings us back to our case study. Members of Cru cannot be considered passive agents of God (rope-makers, to use Rumi’s analogy), who may at best indirectly signify or allude to him. They are precisely those representatives of the religion who are tasked with spreading it.

So we have the problem most clearly expressed like this: how can the delegates from one faith, whose expressed purpose is converting others, engage in an interfaith dialogue which seeks to respect all faiths equally? This is where, I think, a theological analysis can provide some clarification.

A potential solution: radical tawhid

I once posed a question to a good Christian friend of mine. Who is closer to God: a common Christian man, who adheres to all the tenets of the faith but is neither especially involved in his religion nor passionate about his beliefs, or an enlightened Buddhist monk, whose speech and actions shine with spiritual wisdom, so much so that even an atheist spectator might come to consider him, at least, the knower of some secret knowledge?

In typical fashion, his answer was thought-provoking and profound. He conceded that the monk may be closer to God, but that God himself is necessarily closer to the common Christian. Non-Christian religious belief can get one close to the divine, but a connection with God is a two-way relation whose second half is only guaranteed by belief in Christ.

What I intended by this question was to expose a certain kind of paradox underlying not only Christianity, but religious faith more broadly. Almost every belief system considers itself the exclusive, perfected form of divine revelation. In the case of Christianity, this demarcation is intensified by the fact that non-believers are considered incapable of receiving salvation. The stark division in Christianity between the believer and the non-believer is highly unintuitive. It argues that a Buddhist with intense devotion to God and outstanding moral character is still fundamentally deficient compared to even the most sinful of Christians. In essence, it makes godliness the exclusive mark of a Christian and no one else. What can be said about the holy men of other religions? Very little, it appears.

But there is an alternative to this long-standing belief. There may be those who, in a religious analogue to Copernicus, de-center their own religious belief by affirming the validity of other forms of worship and faith. They may do so by interpreting multiple religious traditions as separate manifestations of one underlying logos, or word of God. I often refer to these people — those with a more nuanced perspective on divine reality —followers of perennial religion.

An believer in perennial religion would not necessarily be committed to converting someone of a different faith. They would be the type to encourage a person to explore the depths of his own faith and conception of God, whatever they are, with the understanding that every faith contains treasures of divinity. By the end of this process, an individual may come to prefer one religion over another. But crucially, there is nothing in principle which leads a perennialist to convert another person to a specific religion. The end goal is not a specific creed, but rather a specific person’s connection to God, which could arise from a variety spiritual traditions.

What we have here is a clear theological difference which gives us a fundamentally different position with regards to religious proselytization. And those who believe that perennial religion is a fringe phenomenon are mistaken. Earlier this month I joined some Christians at a Pub Theology event, which seeks to engage Christians and non-Christians alike about philosophical aspects of faith. At one point, the hosts shared with me their sentiment that the ‘knowledge of Christ’ which is considered necessary for salvation is not a literal knowledge of the historical figure of Jesus. Instead, they felt, a person who never knew Christ could still have an ’embodied knowledge’ which may take a completely different outward manifestation from mainstream Christianity. Is this not a clear example of perennialism in action?

I believe that this group is an accurate representation of many religious people in America, who are moving away form the hard-line interpretation of their dogma and towards a more liberal and faith-encompassing spiritual worldview. This is a movement, however, which is frustrated by the orthodoxy: the strict demarcations of separate creeds, each of which prohibits the religious outsider from any legitimate holiness of knowledge of God.

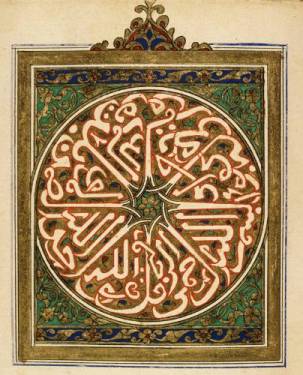

It’s here that I want to introduce the concept of tawhid. The source of this Arabic word is the Semitic root w-h-d, meaning one or unity, and it is often used with the meaning of the English word ‘monotheism’. But tawhid is best understood in the context of Islam, where it is a central (if not primary) tenet of the faith. Islam developed in a region of the Arabic peninsula where polytheism was the dominant spiritual position. The ka’ba, now the destination for millions of Muslims on pilgrimage, was once lined with multiple idols indicating a pantheon of deities. Mohammad, then, was a reviver of the monotheistic Abrahamic tradition which also served as the basis of Judaism and Christianity. For this reason, the renunciation of polytheism (or shirk in Arabic) is a vital part of Islamic belief which goes hand in hand with the call for tawhid, or belief in the oneness of God.

Is perennial religion not, then, the ultimate manifestation of tawhid in our current day and age? To insist on a singular metaphysical source of all world religions is to believe in a oneness that shatters our typical notions of religious difference. It is to believe in a God whose universality transcends specific creeds, places, and eras. It also involves a development of the notion of polytheism. If this modern version of tawhid has an antagonist, it’s the idea that there is not a universal entity which could serve as the common inspiration of diverse religious traditions. In that sense, ‘modern polytheism’ consists, paradoxically, in the idea that a singular religion is the only source of divine truth. It is the position that godliness or holiness does not permeate the whole of human experience and a diversity of cultural groups, being instead isolated to a few specific moments in human history.

A call for a radical tawhid will consist of more than just the presupposition of an underlying God. It will require a deep analysis of many different religions in an attempt to distinguish the legal and practical aspects, which are specific to a time and place, from the eternal aspects, which comprise universal ideas. This is similar to an investigation of religious archetypes, and will be no less difficult . But I believe that we’re up for the task. Certainly, the religious attitudes of more and more Americans are beginning to take a perennial-like form. Our intellectual position with regards to religion needs to catch up to the practical, lived experience of this growing number of religious people.

Conclusion: perennial religion and interfaith dialogue

Are all participants of an interfaith dialogue obligated to adhere to a perennial worldview, which de-centers their specific religion as the exclusive domain of religious truth? Obviously not. This would be an example of exactly the kind of coercion which the perennial mindset is attempting to do away with. A Christian should be given the freedom to believe that all non-Christians have strayed completely and are fundamentally separated from the truth of God. The orthodoxy of organized religion, which does demarcate the lines of spiritual validity in this way, should be respected.

Instead, I want to suggest that a perennial mindset should be an implicit assumption of interfaith dialogue, unless otherwise indicated. That is to say, I believe that the idea that each religion holds some kind of divine truth should be the good-faith assumption of all participants in a religious dialogue. This does not apply, of course, to those conversations or debates which are explicitly intended to contrast the relative merits of different religions. But in every other instance — casual chats, sharing personal stories, and even discussions on theological concepts — the assumption of innate divinity is a healthy and constructive starting point.

Where does this leave our case study from earlier? I believe that the RWA’s stipulation against proselytization should have been replaced with a stipulation of perennial wisdom. This would allow Evangelical Christians to encourage others to join their faith, but only to a certain extent: if the convert-to-be shares his personal experience with what the Christian calls ‘divine’, ‘holy’, or ‘good’, this viewpoint would have to be respected. This can even apply to the nonreligious person, so long as they are able to interpret these words in the context of their own meaningful experiences.

When an interfaith dialogue is centered around the concept of perennial wisdom, there are more opportunities to find common ground and understand the complicated theological ideas at play in all religions. A more universal concept of God helps to shatter the exclusivity and self-isolation that characterizes many more fundamental religious perspectives, and ultimately, will lead to a more positive view of religion as a whole. Finally, it serves to elevate the standard of religious discussion. The clearest sign of an overly-aggressive proselytizer is a disrespect for other religions, and this is a viewpoint which can be remedied by a more nuanced view of the phenomenon of other religions. I believe that we’re due for a radical form of tawhid and the perennial wisdom that it prescribes us.

Hi there,

Please forgive me for not addressing you personally, I couldn’t find your name. I stumbled upon your blog (I don’t recall how) and have listened to both of your podcasts, which I have found to be very stimulating.

I live in London, England, and am very interested in interfaith matters. I have a background as an evangelical Christian, but have always struggled to accept certain aspects of Christian theology, and these days I don’t identify with a particular faith group, though I would still say I am devoted to God.

I thought this article was very interesting and highlighted some of the issues I’ve been considering myself in recent years. I believe that the concept of tawhid is a very helpful one for interreligious dialogue, and I feel that the Shema of the Torah encapsulates a similar idea. On my blog I often encounter Christians who are very zealous and intent on proselytising, and I have found it to be unhelpful (although, admittedly, I used to be somewhat like that myself).

I think the perennial approach is a good one. There is lots of common ground among the world’s major religions. I believe that the key to fruitful interfaith dialogue is holding two ideas in tension – on the one hand the exclusive truth claims of religions like Christianity and Islam, and on the other hand the common ground between such religions (of which there is plenty).

It seems obvious to me that God has a role for every person He has created, and it is someone arrogant when people dismiss the entire spiritual life of millions of people because their beliefs are different. Surely, God has a purpose for everyone He has created (and I would include atheists in that, which I realise is somewhat paradoxical, but I have good reasons for believing this).

I will end there, although there is much more that could be said.

It’s a pleasure to meet you and I’m sure I will enjoy following your blog.

Best wishes,

Steven Colborne

LikeLiked by 1 person

Steven,

Thanks for your insightful remarks. I’m convinced that a growing number of religious people are dissatisfied with the conventional framework of belief, which limits spiritual wisdom to a single tradition. If religion is going to survive the 21st century, it has to take on a new, more universalist form.

Unfortunately, this pursuit is likely to be met with resistance from both sides: from atheists, who will label it a ‘shifting of the goalposts’ and an unwelcome continuation of superstitious belief, and religious people, who will label it a heretical modernization and de-centering of their own spiritual tradition.

But frankly, that just demonstrates to me that there’s something historically necessary about this development.

Take care

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello! I left a comment on this post, but I don’t know if you saw it. Normally comments either appear instantly or say ‘pending moderation’, neither of which happened. I may have done something incorrectly, or perhaps you didn’t want the comment for some reason. I still have it so I can repost if necessary. Please let me know! Steven

LikeLike

hey there! Normally I would get a notification that someone left a comment; I got the one for this comment but not before. I encourage you to re-post it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello! I just tried reposting the comment and it said ‘duplicate comment detected’, which seems to imply it did go through originally 🙃

All I can think is that it could be in your moderation queue or have been marked as spam?

I could always email it to you if we can’t track it down. Does your Contact form work? If not my email address is on my Contact page.

Thanks, and sorry about this!

LikeLike

yup that was it! thanks so much, I’ll respond asap

LikeLiked by 1 person